Explore Collections

You are here:

CollectionsOnline

/

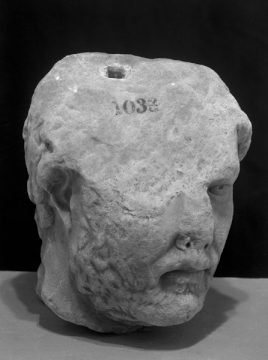

Head of the Roman emperor Hadrian, a fragment of a large relief.

Browse

Head of the Roman emperor Hadrian, a fragment of a large relief.

117-138 AD

Hadrianic

Hadrianic

Greek island statuary marble

Height: 27cm, maximum

Width (mouth): 7cm

Length (ear): 7 cm

Length (inner corner of left eye to left corner of mouth): 9cm

Width (mouth): 7cm

Length (ear): 7 cm

Length (inner corner of left eye to left corner of mouth): 9cm

Museum number: M1033

On display: Sepulchral Chamber

All spaces are in No. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields unless identified as in No. 12, Soane's first house.

For tours https://www.soane.org/your-visit

Curatorial note

This fragmentary head is turned slightly outward and down, in a position similar to the angle it would be represented at in a large triumphal(?) relief intended to be seen from below. The fact that the head comes from a relief can be proved by looking at the relationship between head and neck and the two sides of the head as they must have emerged from the relief background. The identification as Hadrian (117-138 AD) is confirmed by the individual manner of the hair in locks rolled over the forehead and above the ears, characteristic beard, and the expression remaining from left eye and mouth.

The most likely suggestion for the origin of this piece is that it comes from one of the known or lost triumphal reliefs on monuments re-erected in the Imperial capital. In the former category we have the large panels, such as those in the Capitolino and Conservatori collections, from destroyed triumphal arches, and in the latter there are the sundry fragments of such sculpture which can be related or reconstructed, often with the aid of Renaissance drawings. These drawings also show us the number of instances in which the Imperial portrait head, invariably the central feature of these scenes, has been lost and, as often as not, incorrectly restored. Although there appears to be more drillwork in the treatment of hair, the Hadrianic triumphal relief in the Conservatori1 provides a stylistic starting point and is also an example of the wrongly restored Imperial head (sadly, for obvious reasons of headdress and direction, this head cannot belong to it). This relief also confirms that while deeply expressive drilling of the pupils was an innovation in statuary sculpture, such treatment of the eyes was from thsi period the standard procedure on large reliefs of this type.

Beyond the final confirmation of dimensions, what are the facts on which we can rely in a search for the relief from which this fragment comes:

1) the scene must involve a figure of the Emperor Hadrian,

2) the emperor must be bareheaded or wreathed(?) but not, as in the Conservatori relief cited above, veiled or helmeted;

3) The Emperor must face to the right in relief;

4) The relief must be cut from a similar marble to this fragment;

5) If such evidence is visible a check must be made for a continuation of the diagonal break which removed the top of the head into the background. The head, however, could have been broken this way after its separation from the relief. If there appears a likely candidate among unrestored fragments, the breaks may well fit; sadly it is more likely that any candidate that does present itself from the museums of Western Europe will have the area about a lost Imperial head reworked and a new portrait of Hadrian, or (as in the case of the Conservatori panel) another ruler, substituted.

The possibility of connecting this head with the relief of the Emperor making a proclamation from the Arco di Portogallo in the Corso (Rome) would have seemed a likely one on all counts, except for the fact that of this head of Hadrian the moustache and upper lip in situ is said by Wace to belong to the relief, so this Soane head is ruled out on the grounds that it must fit a relief where the complete head has been separated.2

Another possible candidate must be eliminated on the grounds of depth and style of relief, even if we can accept a Hadrianic dating for the disputed imperatorial procession before a large temple, in the Lateran and Terme Museums3.

As an alternative to connecting this fragment with a Roman historical relief, the marble and the peculiarly deep boring of the surviving pupil might point to what is all too rare in our knowledge of such sculpture - a monumental relief from Greece or one of the Hellenistic cities in the Imperial East. The presence in the Soane collection of other sculptures from these areas strengthens such a substitute suggestion.

1 The British School at Rome, A Catalogue of the ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome: The Sculptures of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, H.S. Jones, Oxford, 1926, p. 29ff., pl. 12.

2 A.J.B. Wace, 'Studies in Roman Historical Reliefs' in Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 4, p. 258ff., pl. XXXXIII.

3 E. Strong, E., La Sculture Romana, p. 70ff., fig. 46; Wace, loc. sit., Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 4, p. 247; E. Strong, La Sculture Romana, pl. 72.

The most likely suggestion for the origin of this piece is that it comes from one of the known or lost triumphal reliefs on monuments re-erected in the Imperial capital. In the former category we have the large panels, such as those in the Capitolino and Conservatori collections, from destroyed triumphal arches, and in the latter there are the sundry fragments of such sculpture which can be related or reconstructed, often with the aid of Renaissance drawings. These drawings also show us the number of instances in which the Imperial portrait head, invariably the central feature of these scenes, has been lost and, as often as not, incorrectly restored. Although there appears to be more drillwork in the treatment of hair, the Hadrianic triumphal relief in the Conservatori1 provides a stylistic starting point and is also an example of the wrongly restored Imperial head (sadly, for obvious reasons of headdress and direction, this head cannot belong to it). This relief also confirms that while deeply expressive drilling of the pupils was an innovation in statuary sculpture, such treatment of the eyes was from thsi period the standard procedure on large reliefs of this type.

Beyond the final confirmation of dimensions, what are the facts on which we can rely in a search for the relief from which this fragment comes:

1) the scene must involve a figure of the Emperor Hadrian,

2) the emperor must be bareheaded or wreathed(?) but not, as in the Conservatori relief cited above, veiled or helmeted;

3) The Emperor must face to the right in relief;

4) The relief must be cut from a similar marble to this fragment;

5) If such evidence is visible a check must be made for a continuation of the diagonal break which removed the top of the head into the background. The head, however, could have been broken this way after its separation from the relief. If there appears a likely candidate among unrestored fragments, the breaks may well fit; sadly it is more likely that any candidate that does present itself from the museums of Western Europe will have the area about a lost Imperial head reworked and a new portrait of Hadrian, or (as in the case of the Conservatori panel) another ruler, substituted.

The possibility of connecting this head with the relief of the Emperor making a proclamation from the Arco di Portogallo in the Corso (Rome) would have seemed a likely one on all counts, except for the fact that of this head of Hadrian the moustache and upper lip in situ is said by Wace to belong to the relief, so this Soane head is ruled out on the grounds that it must fit a relief where the complete head has been separated.2

Another possible candidate must be eliminated on the grounds of depth and style of relief, even if we can accept a Hadrianic dating for the disputed imperatorial procession before a large temple, in the Lateran and Terme Museums3.

As an alternative to connecting this fragment with a Roman historical relief, the marble and the peculiarly deep boring of the surviving pupil might point to what is all too rare in our knowledge of such sculpture - a monumental relief from Greece or one of the Hellenistic cities in the Imperial East. The presence in the Soane collection of other sculptures from these areas strengthens such a substitute suggestion.

1 The British School at Rome, A Catalogue of the ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome: The Sculptures of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, H.S. Jones, Oxford, 1926, p. 29ff., pl. 12.

2 A.J.B. Wace, 'Studies in Roman Historical Reliefs' in Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 4, p. 258ff., pl. XXXXIII.

3 E. Strong, E., La Sculture Romana, p. 70ff., fig. 46; Wace, loc. sit., Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 4, p. 247; E. Strong, La Sculture Romana, pl. 72.

Unrecorded

Literature

M. Wegner and R. Unger, 'Verzeichnisse der Bildnisse von Hadrian und Sabina', in Boreas 7, 1984, pp. 105 - 156.

M. Wegner, Hadrian, Berlin 1956, p.101,

C. Evers, Les portraits d'Hadrien: Typologie et Ateliers, Brussels 1994, no 61, p. 129.

M. Wegner, Hadrian, Berlin 1956, p.101,

C. Evers, Les portraits d'Hadrien: Typologie et Ateliers, Brussels 1994, no 61, p. 129.

Soane collections online is being continually updated. If you wish to find out more or if you have any further information about this object please contact us: worksofart@soane.org.uk