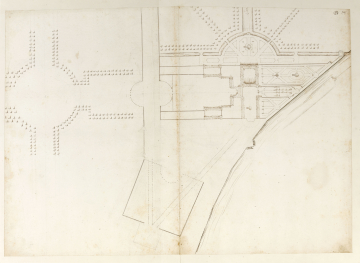

Scale

200 feet to 1 inch

Inscribed

In ink, by Hawksmoor, on right edge of sheet (top edge in volume), Can[al]; and by George Dance at bottom right (top right in vol.), Gd, and below (right) in C19 hand, (4)

Signed and dated

- Undated, but datable to March 1689

Medium and dimensions

Pen and brown ink over incised lines and graphite under-drawing; on laid paper, laid down; 377 x 353

Hand

Hawksmoor

Watermark

Strasbourg Lily/4WR/AJ (Abraham Jansen); Countermark IHS/CDG

Notes

The plan appears to have been developed from initial designs sketched in graphite on the second of two survey plans of the existing palace at All Souls College (Geraghty 2007, No. 205; AS, IV, 5). The All Souls survey plan has a numbered scale bar in Hawksmoor’s hand, and is at least partly in his hand, but it bears outlines in graphite for the quadrant courts attached to the north side of the hall. Linking corridors and long service ranges stretch towards Bushy Park in a large U-shaped courtyard in a plan very similar to that of the northern courtyard in this design. The loose graphite outlines on this part of the survey plan are characteristic of Wren’s exploratory technique and demonstrate his guiding hand in the design as a whole. It is a revision of the first scheme, with a smaller Privy Court, no longer centred on a Council Room, and with the Great Hall retained. The long northern axis of the plan is centred on the Great Hall of the Tudor palace and opens out towards a vast ‘rond-point’ at the intersection of two broad, tree-lined avenues more than a third of a mile (about 2,300 feet) to the north. This northern axis is crossed about half way by the Kingston Road (modern-day Hampton Court Road, A 308), and is so indicated by Hawksmoor on three early plans at All Souls, including AS IV, 4 (Geraghty 2007, No. 204). Kingston is east of Hampton Court across the Thames and a landing here, or by road from Westminster across the Kingston Bridge, would have provided an alternative approach to the new palace, to supplement the historic approach from the river steps on the western side and through the gateways of the Base and Fountain Courts. However, from the emphasis given on this sheet to the river steps and the west-east axis centred on the Long Water, or Canal, and from similar emphasis both in the pencilled sketched plans on the All Souls survey drawings and in the revised Grand Front proposal (Section 1), it is clear that Wren did not intend to the northern approach to take precedence over the western approach; it would have offered an exit from the palace to the hunting grounds of royal park rather than a main entry point. There is nonetheless a strong north-south emphasis running from the royal park through the great hall and fountain court to the gardens facing the river on the south side. The outer walls of the gardens, 650 feet apart, align with those of the west and east fronts and the northern courtyard walls. They define the three main elements of the plan on the west-east axis: the Fountain Court on the west side, 260 feet long, the nearly square Privy Court on the opposite side, also 260 feet across,and linked to Privy Garden on the south, and a central zone 130 feet across occupied by the Great Hall and its narrow flanking ranges. The Hall looks both ways: northwards to the park beyond the service and stable ranges, and south to the central alley of the garden, which is approached by steps from the courtyard. Moreover, the length of the hall governed several of the larger dimensions of the plan. Its overall length on the plan (marked by incised lines and divider points) is 1 1/10 in, or 110 feet. This is the same as the lengths of the flanking blocks either side of the quadrants, half the external width of the Privy Court quadrangle on the north-south axis (220 feet), and a third the overall the width of the inner northern court between the service ranges (330 feet). For the Great Hall, Wren proposed reconfiguring the south side, by removing the central buttress to create a wider central bay with three narrow bays each side. Since the Great Hall is seven bays wide, this proposal would have involved a new external treatment, probably with an applied giant order. The roof would also have been reconstructed. Unlike the plan of Grand Project 1 (Geraghty 2007, No. 206; AS, II,116*), this design does not have an external staircase on the north side of the Great Hall. The main floor level of the Great Hall was some19 feet above the ground. This height determined the principal floor height of the new state rooms and Council Chamber. Whereas in the First Grand Project the transition from ground to first floor level would have been achieved via a grand staircase in the north-west corner of the state apartment quadrant, roughly in the position of the present Queen’s Stairs, here the transition must have been achieved internally. At this stage, Wren has not yet considered a cloister around the quadrangle (see AS,I.10, ST Fig. 129). What is entirely novel about this plan is its presentation, on a single sheet, of a design for palace and gardens as a single entity. In this respect, Wren’s scheme for Hampton Court differs from his design for Winchester Palace. The inspiration appears to come from the plan of Versailles, as drawn and engraved by Israel Silvestre and published in 1680. In Bushy Park, to the north of the palace, is a large square walled enclosure, approached by broad alleys, the lower one from the semicircular screen that closes the western end of the fountain court, and the other on the west east axis that runs across the northernmost end of the palace enclosure. This square enclosure may have been intended as a wilderness, with a maze, or a kitchen garden (see survey drawings of the gardens and park in Section 9).

Literature

Sekler, 1956, pp.159-61; Downes, 1971, pp.81-2; Thurley, 1997, pp.10-11; Thurley, 2003, p.153Wren Society, IV, pl.4

Level

Drawing

Digitisation of the Drawings Collection has been made possible through the generosity of the Leon Levy Foundation