Explore Collections

You are here:

CollectionsOnline

/

Search Results

Browse

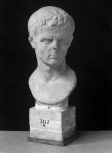

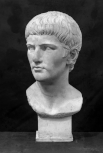

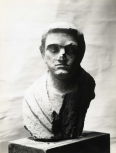

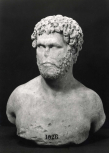

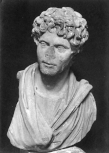

Busts

Browsing 13 items

You are browsing Works of Art & Antiquities

|

Works of Art & Antiquities results view

Works of Art & Antiquities results view

Busts

Browsing 13 items

You are browsing Works of Art & Antiquities

|