Explore Collections

You are here:

CollectionsOnline

/

Roman decorative window panel sculpted on both sides.

Browse

Roman decorative window panel sculpted on both sides.

Early 2nd century AD

Pentelic marble

Height: 33cm

Width: 37cm

Width (excluding restoration): 23cm

Width (frame): 3cm

Thickness: 2cm, maximum

Width: 37cm

Width (excluding restoration): 23cm

Width (frame): 3cm

Thickness: 2cm, maximum

Museum number: M413

On display: Catacombs

All spaces are in No. 13 Lincoln's Inn Fields unless identified as in No. 12, Soane's first house.

For tours https://www.soane.org/your-visit

Curatorial note

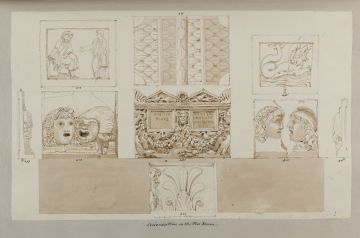

Side A: within a flat frame, an actor with comic mask, in sleeved chiton and cloak, sits facing left on an altar hung with garlands, on which he supports himself with his right arm; the left lies across his lap. His knees, legs, and sandals as well as a female figure with tragic mask, standing left addressing him, are restored. The reverse side, Side B shows a similar comic mask, part of the mouth restored, facing left, at the right above a base moulding, and a restored tragic mask, facing right, opposite.

These reliefs had two functions in Hellenistic and Roman houses, which are the sources for these reliefs themselves as well as our knowledge of such items. A.H. Smith terms such panels, particularly the circular variety, 'ventilator panels'.1 He observes that they served as revolving shutters for window vents. Two of these panels in the Museo Nuovo Capitolino, Rome2, both from the same group and dated early second century AD, are mounted in modern wall-recess installations which still enable them to be moved as in antiquity. Dr. M. Bieber discusses the well known additional use of square and even circular plaques as decorative pillar (or hanging) reliefs3; both are illustrated best by the peristyle of the Casa degli amorini dorati in Pompeii4.

In the ruins of a suburban villa at Pola in Istria (today Pula in western Croatia), one of these oscilla was found in 1936 complete with the iron fastening hook on the top.5

A drawing in the British Museum, a copy of an antique relief showing Dionysius and Icarios (the so-called "Icarios" relief)6 depicts two square plaque-reliefs on pillars in the background. The arrangement of the masks on the reverse here, if we assume correct restoration, has its counterpart in two-dimensional media in a mosaic in the Museo Capitolino.7

The type of our actor seated on an altar, the antique obverse portion of this relief, is copied from a statuary type (known in a number of statuette versions), of a slave from Attic (Greek) comedy8. The masks are restored after a relief similar to that drawn in B.M. Franks.9

The various published (sometimes dramatic) photographs of the partially-reconstructed courtyards in houses around Pompeii and Herculaneum often show these reliefs, rectangular or round, either set on pillars in the greenery in front of columns or (in some instances) hanging from architectural mouldings10.

Soane owned two of these carved revolving panels, this one and Soane number M415. Both are framed and mounted on pivots so that they can be turned to view both sides.

1 British Museum, Guide, 1912, p. 96; cf. fig. 46, no. 2454.

2 Nos. 2129, 2147; compare Mustilli, Museo Mussolini, pls. XXXV f., p. 51f.

3 M. Bieber, Die antiken Skulpturen und Bronzen des königliche Museum Fridericianum in Cassel, Marburg, 1915, p. 45, no. 88, pl. XXVIII.

4 Not. d. Scavi, 1907, pp. 529ff., figs. 1-29.

5 Bullettino dell'Museo dell'Impero Romano (Bull. Mus. Imp. Rom.), Rome, IX, 1938, p. 85, fig. 12.

6 British Museum, Prints and Drawings 1901.0619.2: see T. Schreiber, Die Hellenistiche Relifbilder, pl. XXXVII, and parallels.

7 The British School at Rome, Catalogue of ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome: The sculptures of the Museo Capitolino, ed. H.S. Jones, Oxford, 1912, p. 154, no. 37a, pl. 35.

8 See P. Arndt, Photographische Einzelaufnahmen antiker Sculpturen, Munich, 1893-1912, no. 4131 and bibliography.

9 Dal Pozzo-Albani, I, fol. 149, no. 172.

10 See M. Grant and A. Mulas, Eros a Pompei, Milan, 1974, pp. 48.

These reliefs had two functions in Hellenistic and Roman houses, which are the sources for these reliefs themselves as well as our knowledge of such items. A.H. Smith terms such panels, particularly the circular variety, 'ventilator panels'.1 He observes that they served as revolving shutters for window vents. Two of these panels in the Museo Nuovo Capitolino, Rome2, both from the same group and dated early second century AD, are mounted in modern wall-recess installations which still enable them to be moved as in antiquity. Dr. M. Bieber discusses the well known additional use of square and even circular plaques as decorative pillar (or hanging) reliefs3; both are illustrated best by the peristyle of the Casa degli amorini dorati in Pompeii4.

In the ruins of a suburban villa at Pola in Istria (today Pula in western Croatia), one of these oscilla was found in 1936 complete with the iron fastening hook on the top.5

A drawing in the British Museum, a copy of an antique relief showing Dionysius and Icarios (the so-called "Icarios" relief)6 depicts two square plaque-reliefs on pillars in the background. The arrangement of the masks on the reverse here, if we assume correct restoration, has its counterpart in two-dimensional media in a mosaic in the Museo Capitolino.7

The type of our actor seated on an altar, the antique obverse portion of this relief, is copied from a statuary type (known in a number of statuette versions), of a slave from Attic (Greek) comedy8. The masks are restored after a relief similar to that drawn in B.M. Franks.9

The various published (sometimes dramatic) photographs of the partially-reconstructed courtyards in houses around Pompeii and Herculaneum often show these reliefs, rectangular or round, either set on pillars in the greenery in front of columns or (in some instances) hanging from architectural mouldings10.

Soane owned two of these carved revolving panels, this one and Soane number M415. Both are framed and mounted on pivots so that they can be turned to view both sides.

1 British Museum, Guide, 1912, p. 96; cf. fig. 46, no. 2454.

2 Nos. 2129, 2147; compare Mustilli, Museo Mussolini, pls. XXXV f., p. 51f.

3 M. Bieber, Die antiken Skulpturen und Bronzen des königliche Museum Fridericianum in Cassel, Marburg, 1915, p. 45, no. 88, pl. XXVIII.

4 Not. d. Scavi, 1907, pp. 529ff., figs. 1-29.

5 Bullettino dell'Museo dell'Impero Romano (Bull. Mus. Imp. Rom.), Rome, IX, 1938, p. 85, fig. 12.

6 British Museum, Prints and Drawings 1901.0619.2: see T. Schreiber, Die Hellenistiche Relifbilder, pl. XXXVII, and parallels.

7 The British School at Rome, Catalogue of ancient sculptures preserved in the municipal collections of Rome: The sculptures of the Museo Capitolino, ed. H.S. Jones, Oxford, 1912, p. 154, no. 37a, pl. 35.

8 See P. Arndt, Photographische Einzelaufnahmen antiker Sculpturen, Munich, 1893-1912, no. 4131 and bibliography.

9 Dal Pozzo-Albani, I, fol. 149, no. 172.

10 See M. Grant and A. Mulas, Eros a Pompei, Milan, 1974, pp. 48.

Unrecorded but presumably acquired with M415; both were in Soane's Museum by 1825 when they appear in views of the newly created 'Urn Room', later known as the Catacombs, and appear in a detailed watercolour of a group of objects from that room.

Literature

A. Michaelis, Ancient Marbles in Great Britain, trans. C.A.M. Fennell, Cambridge, 1882, p. 480f., no. 36.

Soane collections online is being continually updated. If you wish to find out more or if you have any further information about this object please contact us: worksofart@soane.org.uk